As the first American businessman to found two Fortune 500 companies in different industries, Eli Broad’s success was defined by keen vision, an appetite for risk-taking and an instinct for strong partners. Over a five-decade career he grew companies that in many ways challenged the industry status quo and positively impacted communities, while experiencing a financial success that would pave the way for his increased political, civic and philanthropic profile.

Eli’s New Stamping Ground: Business

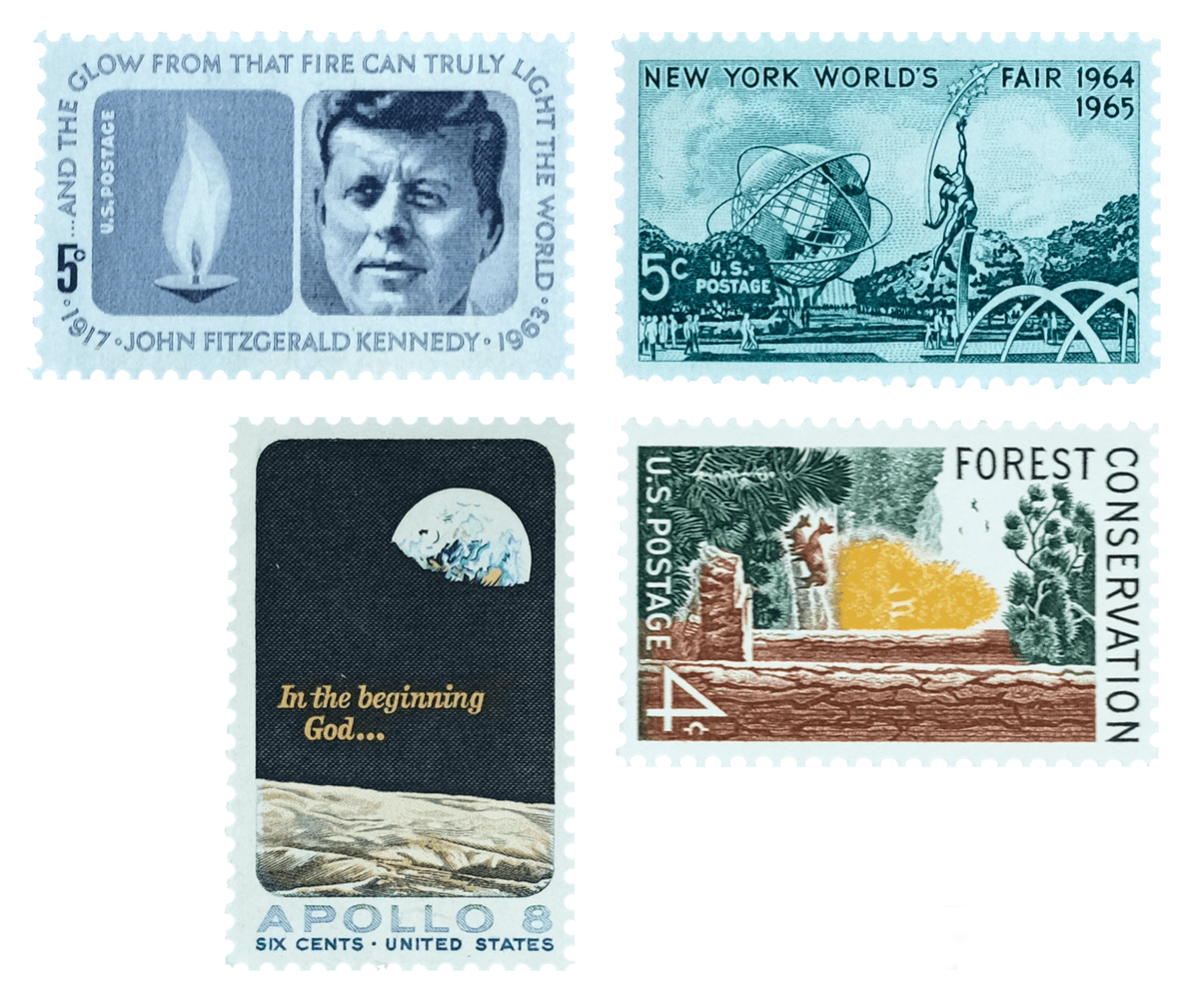

Eli’s entrepreneurial spirit first surfaced in junior high when he, at 13 years old, turned the stamp collection he had started at age five into a profitable venture. Sitting at a folding desk, he placed ads in magazines that earned him up to $100 a month in checks and cash from across the country.

At age 17, Eli found his first employment working at A.S. Beck Shoes and discovered his knack for sales, and the thrill of making a good salary and solid commission—enough to buy himself a green 1940 Chevy, found in the want ads, for $200. Eli continued to work various sales jobs, which included spending the summer of 1953 as a “home modernization salesman” knocking on strangers’ doors selling a relatively new technology: the garbage disposal. He eventually secured an accounting internship to help pay his way through college. After graduation in 1954, Eli started his accounting career, only to be fired from Alfred K. Lubin, his second accounting firm job, which, given his innate sense of independence and leadership, formed his conviction to work for himself rather than struggle under the thumb of a boss.

He never received an explanation for why he was fired but imagined it had something to do with his usual chafing under authority, like his refusal to wear a hat for example. He offered investment advice that Lubin, unlike Golman, simply didn’t want from an employee he perhaps saw as over-excitable and aggressive. And, perhaps worst of all, Eli demanded a raise after passing the CPA exam. So he launched his own accounting practice, using a desk in the office of Donald Kaufman, the husband of Edye’s cousin and a carpenter in Detroit. In exchange for the free office space, Eli offered to do Don’s accounting.

A Lucrative Door Opens in the Homebuilding Industry

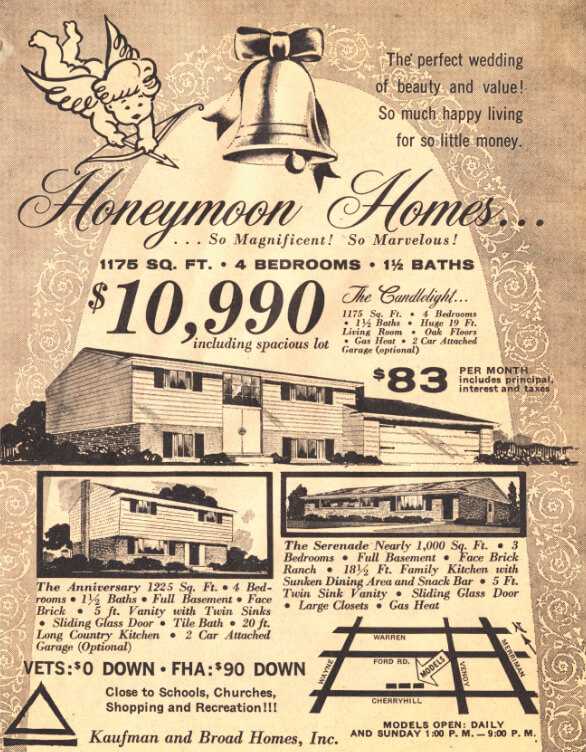

As the homebuilding industry was rising in 1950s Michigan, Eli saw an opportunity to provide even more house design and pricing options to prospective first-time home buyers. This ability to identify and seize opportunities that might otherwise be dismissed by others would serve Eli throughout his career. He dove into the research, pouring over reports and analyses until he had the expertise in pre-fab housing, land use and development investing to propose to Don a homebuilding business that offered more affordable designs young families sought. Because houses were no longer heated with coal they did not need a basement: this design change allowed them to build a house with a mortgage lower than the average rent for young families. Eli drew the floor plan for his and Don’s first home, and construction of the models began the winter of 1956. In a single weekend in 1957, Don and Eli made sales of over $200,000, and Kaufman and Broad Home Corporation was officially in business.

Eli presenting a new home design for Kaufman and Broad

That first year, Kaufman and Broad achieved sales of $1.7 million from 120 houses, and by the end of 1959, they were among Detroit’s biggest builders. The decision to expand Kaufman and Broad, ambitious though it was, came as much from caution as from confidence. Eli wanted to balance out the inevitable downs of the business cycle of Detroit and also grow the company. Though he let himself imagine becoming a national homebuilder, he was still too careful to proceed into several markets, or even a single especially challenging one, simultaneously. One additional market, Eli thought, if he moved there himself to ensure the company stuck to its fundamentals, could keep the business going even if Detroit’s housing market declined.

Throughout his life, Eli had been relatively incapable of idle. Though by age 26 he had made a small fortune and created a life far better than anything he had imagined growing up, he was compelled to keep going.

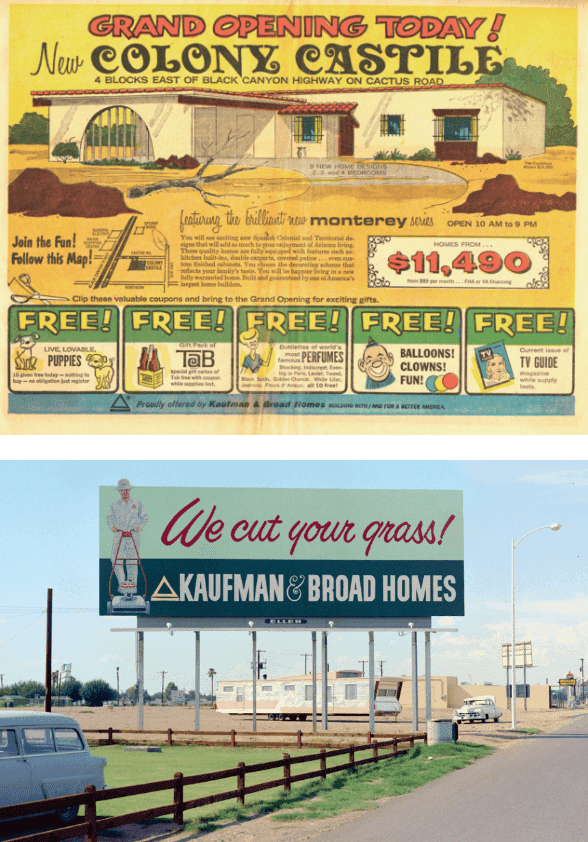

All the cities Eli considered for an expansion were in warmer climates, promising to balance the slow winter months of Detroit and follow the tide of American migration from north and east to south and west: the Atlantic coast of Florida, Southern California and Phoenix, Arizona. At the time, Phoenix held the most promise of the three locations—like Los Angeles but on a manageable scale. By 1960, when Eli was considering his move, the city was home to nearly 300 manufacturing operations, including Motorola, General Electric, Kaiser Aircraft and Electronics, Goodyear and the electronics company, Sperry Rand. The city annexed outlying land to build vast suburbs; three in four Phoenix residents lived on land annexed in the last decade. Housing starts were estimated at 16,700, large enough a number to attract even the biggest builders in town. In 1960, Eli and Don partnered with another Detroit builder, Pappy’s Homes, to make the move to Phoenix, going 50-50 and eventually buying the other company’s share, hiring its principals and once again targeting first-time homebuyers with two-, three- and four-bedroom homes starting at the far-lower-than-Detroit price of $8,990, the lowest price in the market. Eli and Edye also moved their family to the city.

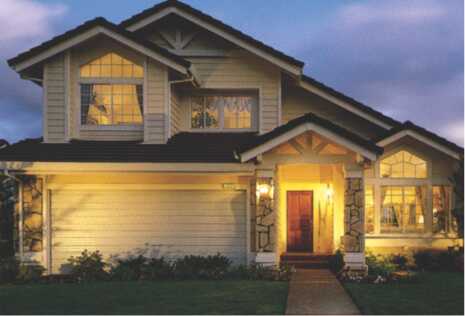

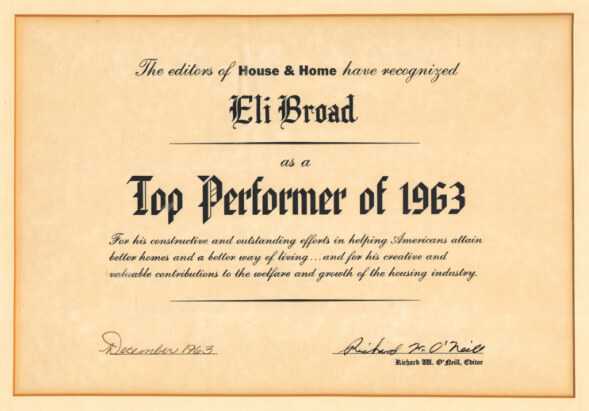

In 1962, Eli would once again move his family, this time to Los Angeles, California, a new market for Kaufman and Broad. Los Angeles was in many ways a homebuilder’s city, built on land grabs and real estate booms. Its scope initially confused but finally compelled Eli because of its potential and its relatively long history of welcoming builders. In the winter of 1963, Eli focused fully on his company’s first development in the new market, introducing an innovation for the region: the townhouse. Their first housing development there, The Huntington Continental townhomes, became an undeniable success, helping Kaufman and Broad ascend the ranks of homebuilders to join the rare multi city, financially strong companies—and it had accomplished it in only six years. Promising security and assistance to his customers, Kaufman and Broad continued development throughout Southern California, and became the first homebuilder in the state to introduce the graduated mortgage.

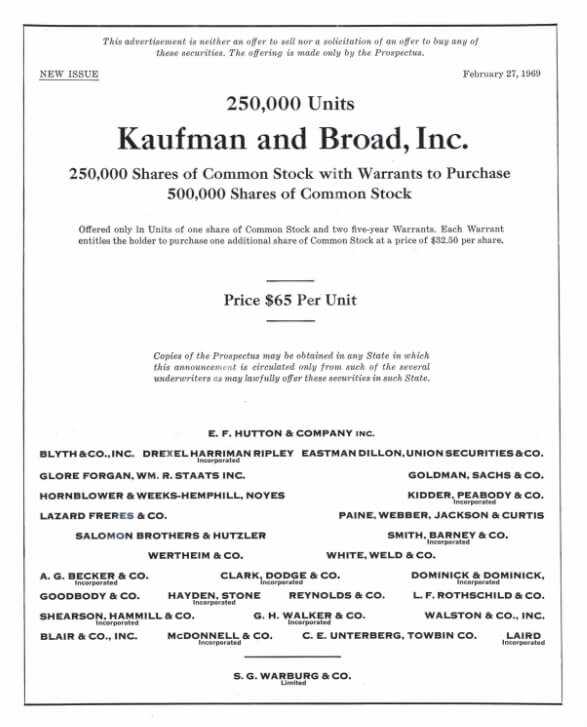

Kaufman and broad building company go public

On November 8, 1961, Kaufman and Broad Building Company also became the first homebuilder to go public on the American Stock Exchange, with Eli named president and Don as executive vice president. After one year as a public company, Kaufman and Broad was listed among the 200 fastest-growing businesses. That same year, the Kennedy administration established Section 221(d)(3) of the National Housing Act to encourage for-profit and non-profit developers to build housing for moderate-income families who didn’t qualify for public housing and couldn’t afford suburban housing; Kaufman and Broad was recognized as one of the first homebuilders to pursue this program which initially paved the way for over 200 homes on sites cleared of substandard housing, with monthly payments less than those associated with standard mortgages.

Kaufman and Broad’s acquisitions, new market launches and diversification were key to the company’s impressive growth over the years, and Eli foresaw continued profits due not just to aggressive growth plans and the company’s expansion, but also to an increase in jobs and household formation, the prime generator of home sales, because a group Eli called “post-war babies” was beginning to come of home-buying age.

Eli was “setting a blueprint for professional builders across the land . . . and creating a mood and feeling for good living.”

—National Association of Home Builders (NAHB)

One such diversification opportunity came in the form of cable television. Eli began researching less interest-rate-sensitive companies to acquire that fell outside of his main line of business but were related to it. That was a conservative strategy for 1960s Wall Street—when conglomerates were growing based on the theory that a good manager could manage any kind of company—and it led Eli to a bold diversification, forming Nationwide Cablevision late in 1966. Cable television was a new technology, promising to deliver customers’ favorite programming without the static, which was a particular nuisance in the less-developed suburban areas where Kaufman and Broad built homes. Cable television was distributed through a network of underground cables linked to homes which were often laid as they were being built. Eli secured a $12 million line of bank credit, which increased the company’s available capital to $25 million, and sold $5 million worth of convertible debentures to pursue the Nationwide Cablevision acquisition.

But Eli found it too capital-intensive and he fretted over increasing Federal Communications Commission regulation. The company sold its fledgling cable division to Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI), for a 15 percent share of that company’s stock. Eli immediately cashed his shares in for $23.5 million—a handsome profit at the time but nothing compared to the billions TCI would be worth as part of Comcast a few decades later. Not long after the sale, new rules emerged from the Federal Communications Commission that helped the cable business begin a long boom. The industry would soon be connected to most every American household, as the cable lines streamed dozens of new television stations. Eli would later joke that it was his biggest mistake in business: he should have kept cable and sold homebuilding.

In May 1969, Kaufman and Broad’s shares were listed on the New York Stock Exchange. Eli, just shy of turning 36, was the youngest CEO to ever run an NYSE-listed company, and Kaufman and Broad became the first pure-play homebuilder on the Big Board. That same year, they achieved record sales of $100 million, and Eli, as part of a strategic growth strategy, set his eyes once again on acquiring a company in an entirely different industry. To help focus his search, he turned to the country’s worst economic period, the era of his birth. Eli and a small executive team combed histories of the Great Depression, searching for which type of companies survived. That, Eli decided, was the type of company he wanted to own—one that would keep his business afloat in the worst of times, and one that wouldn’t raise heckles on Wall Street for being a risky acquisition. Builders collapsed when land grew too expensive, or when people stopped buying homes. Mortgage companies, savings and loans, thrifts and banks all went under. The only companies that survived, it seemed, were life insurers.

From a financial perspective, Eli realized that buying a life insurance company was a smart move. Home sales generally suffered during times of deflation, but life insurance was a hedge against deflation, and still enough of a necessity to buy during times of inflation. Life insurance companies, unlike commercial banks, savings and loans and real estate investment trusts, had a steady, long-term flow of income. They faced no geographic limits on investments, like savings and loans often did. Though other types of companies promised more potential payoff and more flash, they had less flexibility and were less secure.

There was also a personal motivation to embrace the industry: just like with building and selling homes, Eli believed that developing life insurance products was about empowering Americans with tangible assets and a vehicle for individual wealth creation. So, working with brokers, Eli hunted for a good-sized, well-run insurer that was not a mutual. (Buying a mutual would require Eli to split profits among policyholders rather than keeping them invested at the corporate level.) The first suitable company Eli found was the one he would acquire: Sun Life Insurance Company of America.

The Dawn of SunAmerica

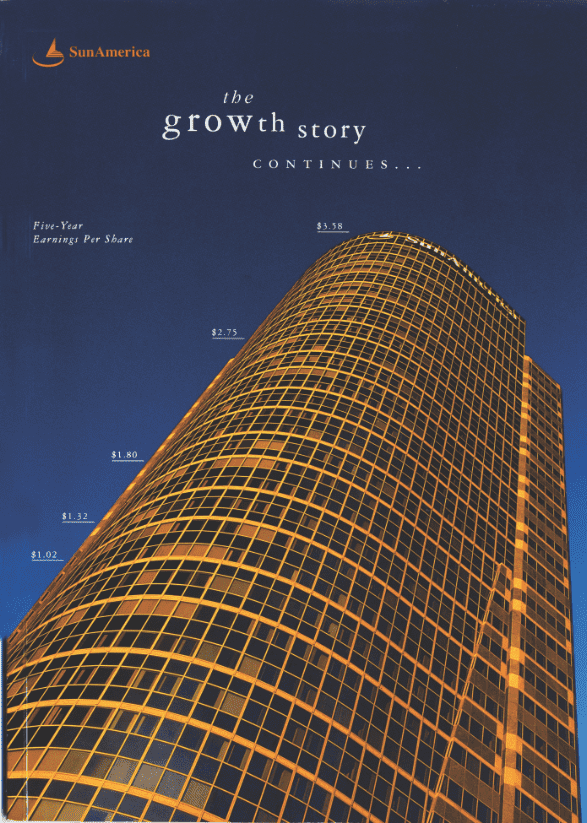

The acquisition announcement came on July 6, 1971 and was finalized that fall: Kaufman and Broad would pay 10 times Sun Life earnings, with a combination of cash and common and preferred stock, for $52 million. Eli became fully engrossed in transforming Sun Life: He built a marketing department, hired more independent agents, expanded the number of regional sales directors and pushed into six new states for a total of 44. They offered new products, including life insurance that was linked to equity, seeking a niche for Sun Life that would distinguish it among the life insurance giants. In 1988, Eli changed the name to “SunAmerica,” to better express the company’s national scope and optimistic outlook, and unveiled their new sundial logo.

SunAmerica advertisement

In March 1993, SunAmerica launched its most successful and innovative product to date, a signature new variable annuity called Polaris, enabling policyholders to switch from variable to fixed rate depending on the market. At the end of 1993, SunAmerica had already reached one of its mid-decade financial goals: it held $23 billion in assets.

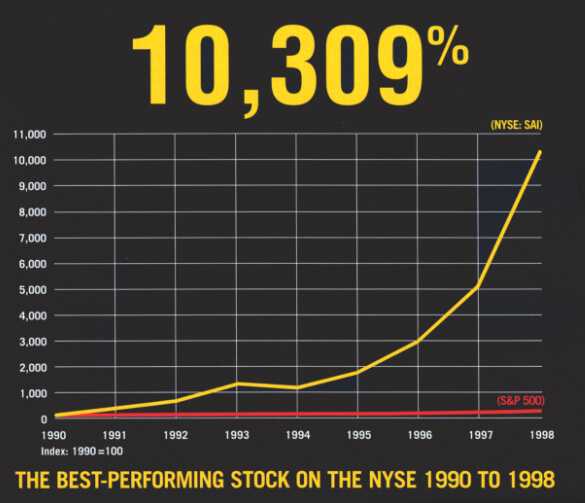

SunAmerica’s run in the 1990s, and really since its founding, relied on two key strategies: acquisitions and internal growth. Eli had a knack for hiring good people and motivating them to deliver their best work. The company went from $12 billion in sales in 1990 to $85 billion in sales in 1997, doubling its market share in variable annuities. SAI was the best performing stock on the New York Stock Exchange from 1990 to 1997. The tally vaulted SunAmerica onto the very ranking Eli so often measured himself against: the S&P 500.