From an early age, Eli Broad understood that government plays a powerful role in determining the life experience of its citizens. As a philanthropist, he believed that he could help communities by piloting or supporting programs with data and metrics as proof points that the government could go on to adopt permanently.

California Governor Gray Davis, Los Angeles Mayor Richard Riordan and Eli with others celebrating the Democratic National Committee’s selection of Los Angeles as the site of the 2000 Democratic Party’s Nominating ConventionPolitical Engagement

Though he identified as a Democrat, Eli was not concerned with party affiliation when it came to ideas and strategies that would most positively impact communities he sought to serve. Particularly in the latter half of his life, Eli befriended and worked with leaders at all levels of government—from U.S. presidents and their administrations, to federal, state and local officials, including nearly every mayor of Los Angeles since he moved to the city in 1962. Over time, he became as savvy in politics as he was with business and art, leveraging connections and opportunities to affect meaningful change.

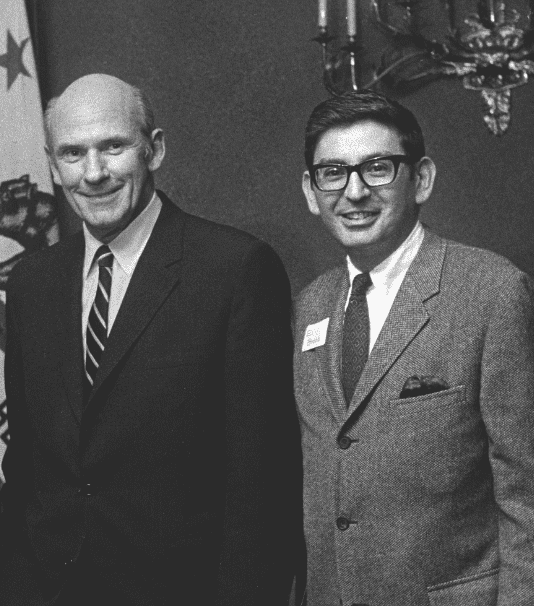

Eli was first introduced to the role of government and politics when he attended rallies and parades as a young boy with his father, Leon, who wanted to encourage in his son a love of liberal politics. But it would not be until Eli’s involvement in the Alan Cranston race decades later that he changed his perspective on politics—and discovered his role within it.

The Alan Cranston Race

After the Watts riots in 1965, Eli moved to expand Kaufman and Broad’s efforts nationwide by creating a subsidiary, Homes for a Better America. He believed that increased homeownership by families left out of the suburban home-buying boom would help stabilize and calm American cities. To run his subsidiary, Eli found a high-visibility leader for the effort in the former state controller under Governor Pat Brown, Alan Cranston. After hearing Eli’s pitch, Alan agreed to take the job, and Homes for a Better America launched in March 1967. The two men worked with the recently appointed secretary of the new Department of Housing and Urban Development, Robert C. Weaver, who wanted to work with them to create a new model of public-private homebuilding efforts.

Homes for a Better America was short-lived, however, because Alan decided to run for the U.S. Senate in California. He asked Eli to be his campaign chair. Eli still had the rest of Kaufman and Broad to run, of course, but Alan’s offer intrigued him, and he decided to help. He liked and agreed with Alan’s politics: He called for an end to racial and class discrimination, a reduction of hostilities in Vietnam and full nuclear disarmament: a devotedly liberal platform in an election that would require an appeal to independent and centrist Republicans as well as Democrats in order to win. Eli admired that Alan stuck to his progressive views, and his willingness to take on a difficult race.

Eli began a careful study of how to run a campaign: how to organize the campaign’s hierarchy, utilize its offices and divvy up a budget, voter habits in primaries and general elections and learning registrant profiles and trends. He called people he knew, and people he did not, for advice. Eli traveled with Alan whenever he could as the candidate gave speeches across the state, answering questions about his positions on the escalating draft, the floundering Paris Peace talks, the heightened tax burdens that came with war and the poverty marches Martin Luther King, Jr. was leading in Washington. Eli and Alan were together in San Francisco when King was assassinated on April 4 in Memphis, Tennessee. On June 4, Alan handily won the California Democratic primary. Alan, Eli, Edye and other campaign leaders watched returns on television in a suite at the Ambassador Hotel, where seemingly every Democrat and politicon in the state had gathered to hear Robert Kennedy speak. Four hours after the polls in California closed, Kennedy claimed victory, giving a rousing speech just after midnight. Eli, Edye and Alan were in their suite when the fatal shot was fired. Television reporters announced that Kennedy had been shot and the hotel went on lockdown . . . Eli held Edye’s hand as they rushed downstairs and toward the exit.

By mid-July, Eli was overseeing a $1.7 million budget for statewide operations with rigor, ensuring that every donor’s dollar was used effectively. He also established rules for campaign operations, including regular, efficient and punctual meetings at campaign headquarters. Throughout the summer and into fall, Eli continued to tour the state with Alan, attending speeches and arranging meetings, learning the often-difficult lessons of politics. When it came to dealing with the press Eli was comfortable in this role: he was terse without being unfriendly, dry without being dull, straightforward sometimes to the point of excessive candor and constitutionally unable to say no to a photographer. But what worked in business did not necessarily translate to politics. Eli lacked the politician’s silver tongue, and could not help saying exactly what he thought. Although Alan won the race, Eli was left somewhat disillusioned by the politics of a campaign. Even if his chairman position was akin to a chief executive, it was far from it—Eli had a boss in Alan, and Alan had a boss in the voters. Eli did not like answering to other people—he was too willful to work for someone else. The lessons he learned working on Alan’s race would serve him well for the rest of his career as a businessman and philanthropist.

Working for the Cranston campaign was Eli’s first public engagement outside business and significantly elevated his profile in California

Eli’s Political Relationships and Friendships Across the Aisle

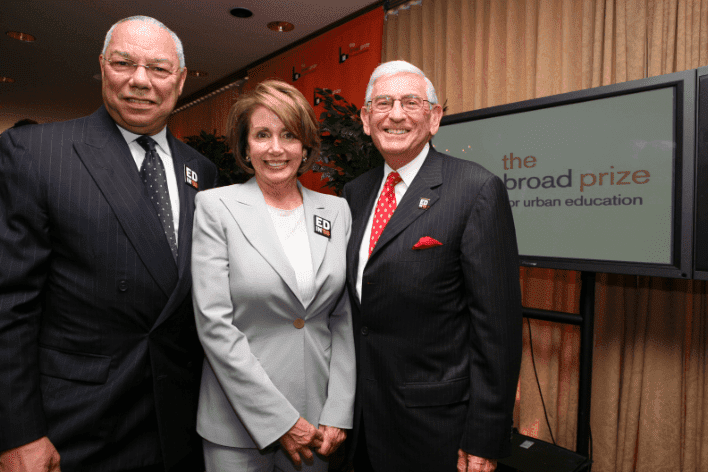

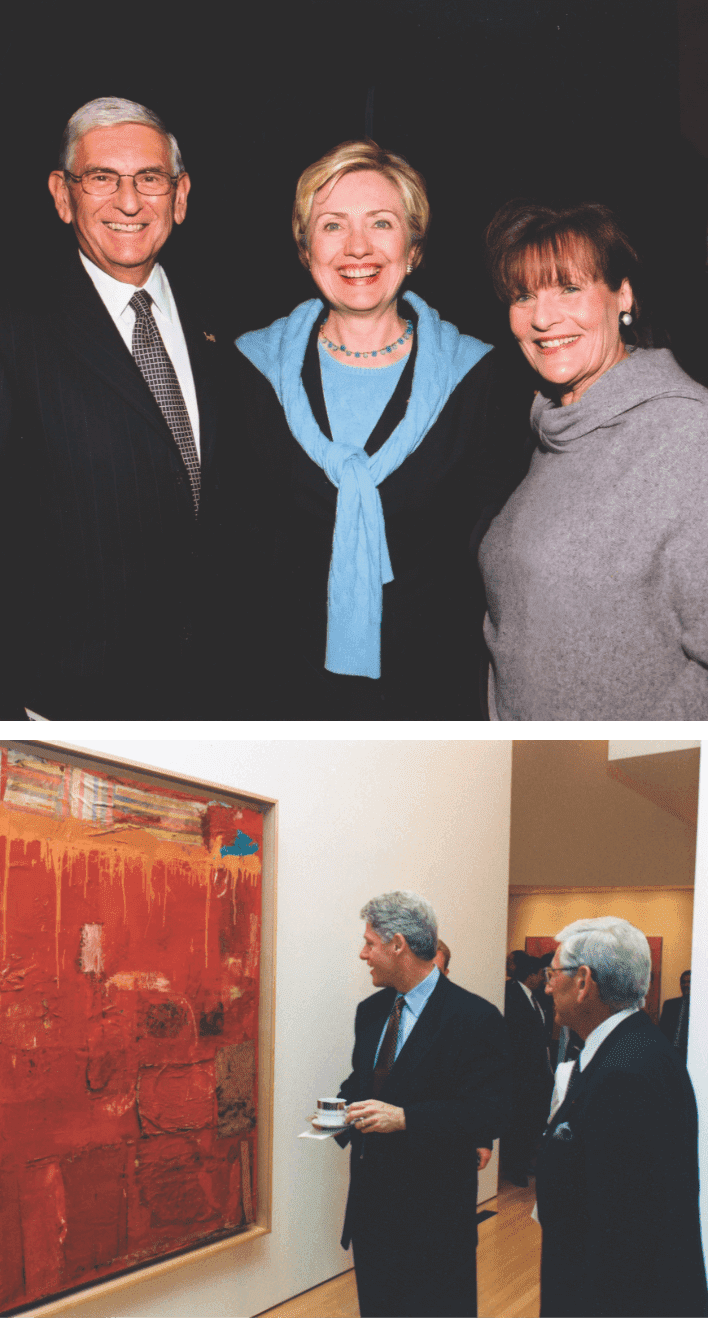

A lifelong Democrat, Eli sought out strategic relationships, many of which evolved into genuine friendships, with politicians and government officials from both parties, including Bill and Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama, Al Gore, Arne Duncan, Rod Paige, Margaret Spellings, Barbara Boxer, Dianne Feinstein, John Kasich, Nancy Pelosi, Mike Bloomberg, Richard Riordan, Antonio Villaraigosa, Mark Ridley-Thomas and Fabian Nunez, among many others. With his usual desire to be near the pulse of anything—business, the art world, politics, a party—it was not unusual for Eli to be hosting an inaugural activity, participating in meetings at the White House, or dining at a state dinner.

Reimagination of Grand Avenue

An important focus of Eli’s civic work in Los Angeles was to give his adopted home city what he had always believed it lacked: a strong center. As Disney Hall on Grand Avenue made progress, Eli and Mayor Dick Riordan began to discuss the prospect of redeveloping the Grand Avenue corridor. By the end of 2001, along with his friend and former Sacramento Kings co-owner Jim Thomas, Eli was co-chairing the Grand Avenue Committee as they navigated a range of challenges facing the project: from design and planning, to budget and resource allocation disagreements, to wavering public and community support. By the end, Eli would work alongside L.A.’s former mayors, Riordan and Hahn, Mayor Villaraigosa, as well as teams of planners and builders. On July 26, 2012 Grand Park, the first installment of the Grand Avenue Project, opened to the public.

Education reform initiatives

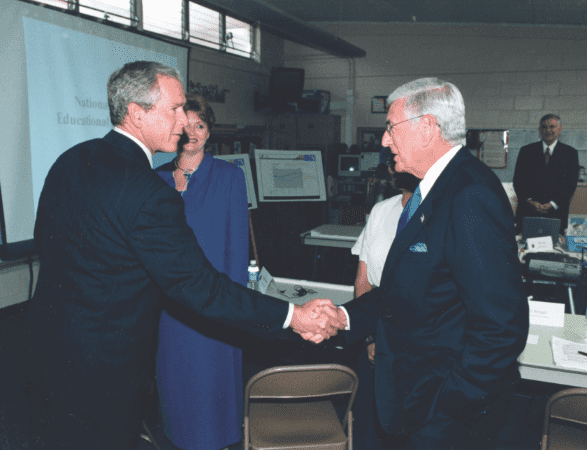

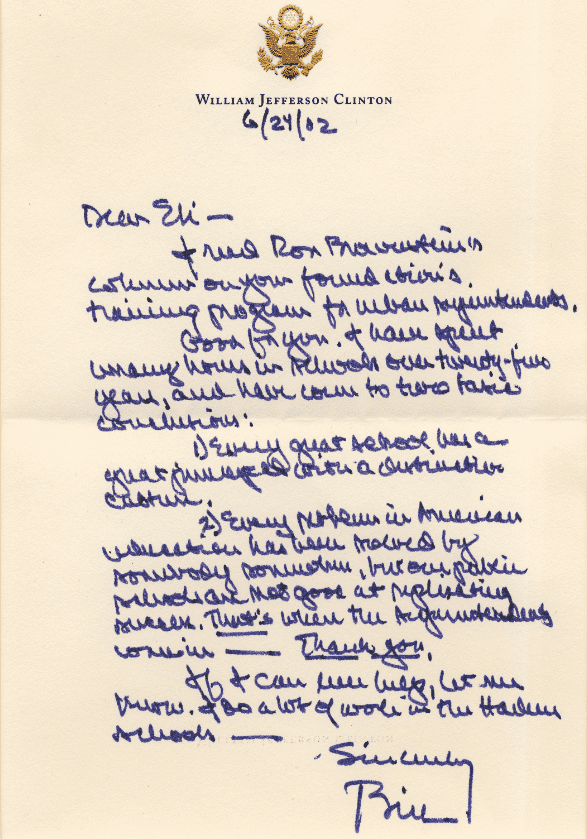

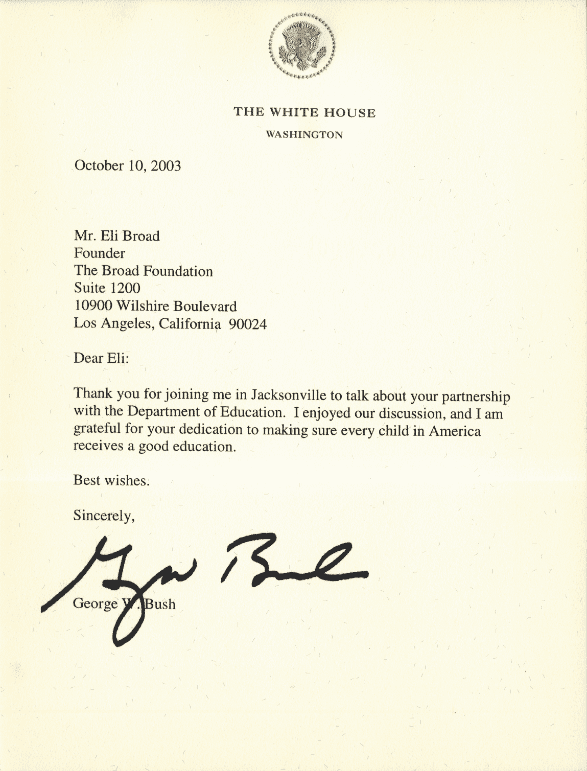

Believing that education is not a partisan issue, Eli connected with politicians at all levels who shared his passion for education reform. In the early 2000s, Eli worked with Rod Paige, the seventh U.S. Secretary of Education, and the Bush administration on the development of the Student Information Project (SIP), which was designed as a national database of information for parents on school data. He also built the SIP in Michigan alongside Governor John Engler. Both the endeavor and the relationship were especially meaningful to Eli as the Broads always kept a pulse on Michigan’s politics, visiting their home state regularly.

Eli continued to focus on partnering with local officials to improve public schools in Los Angeles. He helped recruit Roy Romer, the former governor of Colorado, to serve as the superintendent of the Los Angeles Unified School District from 2000 to 2006 when he led the largest school construction program in the country, securing state and local bond money. By the time Antonio Villaraigosa became Mayor in 2005, Eli had known him for well over a decade through his work in the California State Assembly. Once he ascended to the city’s top office, Antonio met with Eli regularly, often to discuss education reform. Ultimately, Antonio effectively ended his, Eli’s and other reformers’ advocacy of mayoral control of the Los Angeles Unified School District when he accepted a deal that gave the mayor’s office oversight of just a handful of the worst-performing schools.

At the national level, Eli partnered with the U.S. Secretaries of Education in President Bush and President Obama’s Administrations to advance policies and programs that would improve public K-12 education.

The 2020 Election

In early 2020, nearly four years into the Trump administration, Eli felt a deeply embedded sense of urgency to support democracy and bring new leadership to the White House. At age 87, Eli was alarmed by the climate crisis and the perilous state of America’s democracy. Leading up to the November 2020 election, Eli and Edye doubled down on their political contributions giving to Presidential, Senate and House candidates with strong records on climate change, supporting organizations that worked to mobilize, educate and protect voter rights; and seeding a national education and awareness campaign that elevated the issue of climate change. In one of his final public acts, Eli wrote an op-ed in support of a wealth tax published in The New York Times, writing:

Two decades ago I turned full-time to philanthropy and threw myself into supporting public education, scientific and medical research, and visual and performing arts, believing it was my responsibility to give back some of what had so generously been given to me. But I’ve come to realize that no amount of philanthropic commitment will compensate for the deep inequities preventing most Americans—the factory workers and farmers, entrepreneurs and electricians, teachers, nurses and small-business owners—from the basic prosperity we call the American dream . . . The enormous challenges we face as a nation—the climate crisis, the shrinking middle class, skyrocketing housing and health care costs, and many more—are a stark call to action. The old ways aren’t working, and we can’t waste any more time tinkering around the edges.”

—Eli Broad